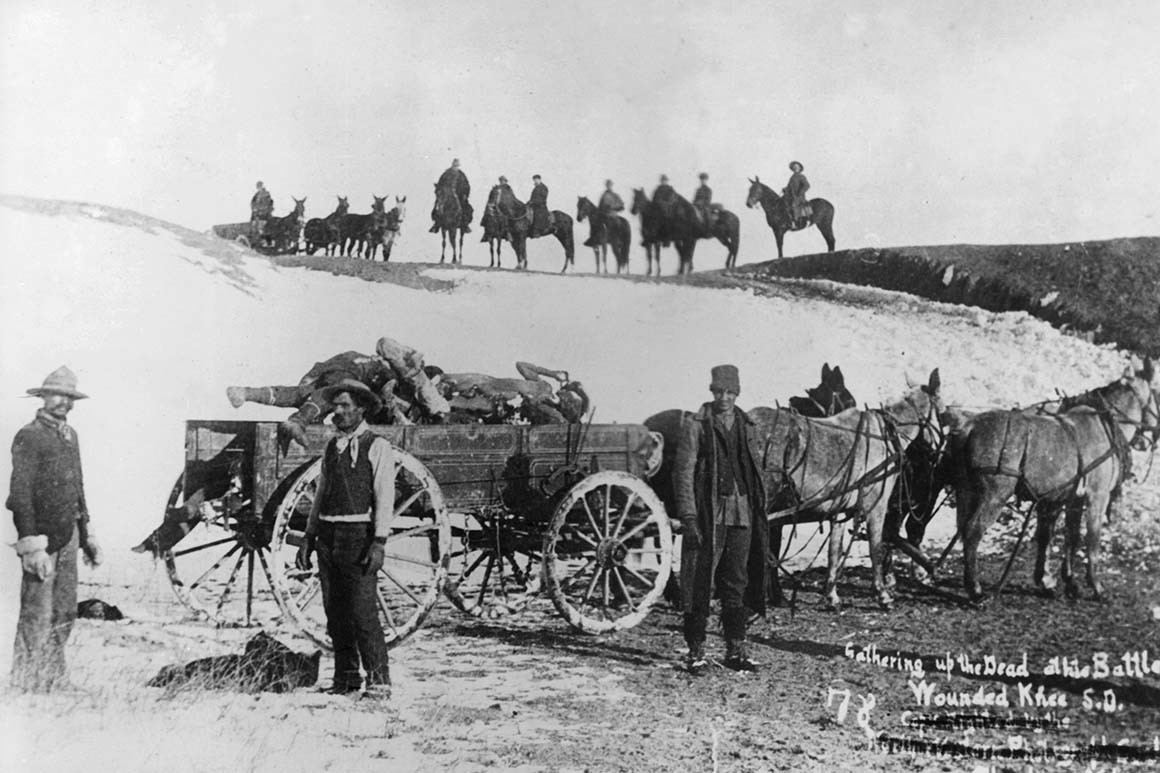

Bodies frozen in the snow, a baby with five bullet wounds, small children shot at such close range their clothes and bodies were singed with gunpowder. Army general Nelson Miles was shocked by what he found at Wounded Knee. He arrived several days after the carnage, which occurred December 29, 1890. A battle-hardened Civil War veteran, he was appalled by what he called in a letter to his wife, “the most abominable criminal military blunder and a horrible massacre of women and children.”

Over Miles’ objections, 20 Congressional Medals of Honor were soon awarded to U.S. Army soldiers involved. When more medals were suggested later in 1891, Miles called them “an insult to the memory of the dead.”

Five U.S. Representatives are co-sponsoring a bipartisan bill called the Remove the Stain Act, which seeks to rescind the Wounded Knee awards.

Speaking at a June 25 Washington, D.C., press conference were two-time Purple Heart recipient and retired Marine colonel Paul Cook (R-Calif.), Deb Haaland (D-N.M.), and Denny Heck (D-Wash.). Both Haaland and Cook are members of the House Armed Services Committee, to which the bill was referred after being submitted to the House.

The bill, H.R. 3467, needs to get through the committee and pass both the House and the Senate in order to be sent to the President’s desk for his signature. According to Oliver “OJ” Semans, a member of the Rosebud Sioux and the co-executive director of the voting-rights group Four Directions, efforts are now underway to increase the number of House co-sponsors and to craft a companion Senate bill.

That December day in 1890, a unit of the Seventh Cavalry had accepted the surrender of a group of Miniconjou Lakota. According to historian Jerry Green in a paper for the Nebraska State Historical Society, the soldiers disarmed the Lakota and butchered them. Green reports one officer present describing the soldiers as “greatly excited,” shooting the Lakota wildly without aiming their guns. “Warriors, squaws, children, ponies, and dogs…went down before that unaimed fire,” according to one officer. As many as 375 died, about 200 of them women and children, according to later Congressional documents.

The soldiers also killed or wounded dozens of their own comrades positioned across the surrounding circle. “It was impossible not to,” according to an Army medical officer present, says Green’s research.

Later that night, a surgeon who had served in the Civil War tended to Lakota survivors. He began to look faint, according to a Nebraska journalist who was among those who had arrived to report on the incident. “This is the first time I’ve seen a lot of women and children shot to pieces. I can’t stand it,” the journalist reported the surgeon saying.

At the Washington, D.C., press conference, Rep. Haaland said introduction of the bill “shows that our country is finally on its way to acknowledging and recognizing the atrocities committed against our Native communities.” One of the first Native American women to serve in Congress, Haaland, who is a member of Laguna Pueblo, lauded the continued strength of Native people, despite the many outrages against them, including Wounded Knee.

From left, standing, U.S. Representatives Paul Cook (R-Calif.), Deb Haaland (D-N.M.), and Denny Heck (D-Wash.) with, seated, WWII Army veteran Marcella LeBeau, of the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation. They are in the Longworth Capital Building, in Washington, D.C., to speak about the Remove the Stain Act, a bill to rescind Congressional Medals of Honor awarded for the Wounded Knee massacre. (Photo by OJ Semans.)

Rep. Cook condemned not only the massacre but “the continuation of a lie that is associated with the highest award we have for valor.” With the Act, he said, “We are […] correcting something that was tragic in all ways [including] awarding those particular medals.”

Rep. Heck called the bill a step toward healing. He noted that his congressional district once had the highest number of living Congressional Medal of Honor recipients of any district in the nation.

“We have distinguished people here to help our ancestors,” said Manny Iron Hawk at the press conference. A descendant of a massacre survivor, he is from the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation. “Today we give our ancestors voice,” said Marlis Afraid of Hawk, also a descendant of a Wounded Knee survivor. “It’s time to heal.”

This “darkest day” is not recognized or taught in our schools, said descendant Phyllis Hollow Horn, born and raised in Wounded Knee, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. She saw a connection between the press conference’s date — June 25, the anniversary of the Battle of the Little Big Horn — and the soldiers’ uncontrolled fury at Wounded Knee. She said they sought revenge for the Lakota and their allies defeating the Seventh Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn just 14 years before.

In early January, members of the 7th Cavalry gather up the frozen bodies of the Native people they massacred at Wounded Knee on Dec. 29, 1890.

The descendants spoke of the enduring pain of the killings and its continued presence in their communities. Nowadays, Native women experience extreme rates of violence, including murder. Meanwhile, Native children have long been a focus of federal policies of forced assimilation and genocide. To begin with, they were among massacre victims — at Wounded Knee, at Sand Creek, in Colorado, on the Marias River, in Montana, on the Bear River, in Idaho, and in other places. Starting in the late 1800s, they were sent to notoriously abusive boarding schools established to eradicate Native culture. Today, many states take Native children into foster care or adoption in numbers that are disportionately higher than their percentage of the population.

“As a grandmother and great-grandmother, I’m supporting this bill for the children — to ensure that no one hurts our children again,” said Hollow Horn.

The press conference celebrated World War II veteran Marcella LeBeau of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, in South Dakota. She has long advocated for rescinding the Wounded Knee medals. Decorated for saving lives rather than taking them, LeBeau, now 99, received France’s highest award, the Legion of Honor, as well as U.S. and Belgian awards, for her work during the war. A U.S. Army lieutenant and surgical nurse, she cared for those injured on D-Day and was often near the front lines. At the Battle of the Bulge, she could see enemy planes overhead, hear guns firing, and feel bombs shake the ground as she tended the wounded.

LeBeau is among the many Native Americans who have served in the military. They are the population group with the nation’s highest enlistment rate, according to the Department of Defense. In a Library of Congress interview, LeBeau called her World War II service “one of the greatest honors and privileges of my life.” Of the soldiers she served with, and saw both live and die, she said, “They were honorable men, protecting our country” — making clear the vast gulf between them and the soldiers at Wounded Knee.

OJ Semans, a Navy veteran as well as co-executive director with his wife, Barb Semans, of the voting-rights group Four Directions, was instrumental in marshalling support for the Remove the Stain Act from the three Congressional co-sponsors. He says that Native Americans’ recently improved ballot-box access, especially in states critical to the outcome of the 2020 election, means public officials will now listen to their concerns. (For more, see In These Times here, here, here and here.)

Though not one of the three House members now co-sponsoring the Act, U.S. Representative Dusty Johnson (R-S.D.) sent In These Times a written statement. “Medal of Honor recipients of today are held to a tremendously higher standard,” wrote Johnson, in whose congressional district the massacre occurred. “It’s painfully clear from our history [that] the U.S. didn’t have these same standards in 1890.”

Recipients of the Congressional Medal of Honor receive their award from the President, who presents it on behalf of Congress. With that in mind, Semans has written to the President about the Act, urging him to “[r]estore honor to the Medal of Honor itself, to the brave soldiers who have earned that Medal in real wars, against real enemies.” At press time, In These Times had not received a response to a request for a comment from the President, who has used a reference to Wounded Knee as a slur on Twitter.

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society says it represents recipients. President Dwight D. Eisenhower established the nonprofit society in 1958 “to protect, uphold and preserve the dignity and honor of the medal at all times and on all occasions.” Honor Society spokesperson Laura Jowdy said she could not comment on the Remove the Stain Act. She cited prohibitions against society involvement in legislative affairs.

The medal, though exceptionally prestigious nowadays, has a checkered history. During 1916 and 1917, General Miles headed a Congressional inquiry into criteria for bestowing it. He found it could be doled out haphazardly. Clerical errors spawned medals. Miles’s inquiry revoked 864 medals that had gone to Civil War soldiers not for bravery, but to encourage reenlistment.

In his research for the Nebraska State Historical Society, Green found that some of the soldiers awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Wounded Knee may have faked or exaggerated wounds in the process of qualifying for the award. At least one other recipient was endorsed by a group of friends. Some medals appeared frivolous, including one for “conspicuous bravery” in rounding up a runaway pack mule. A company musician who got a medal had been court-martialed eight times. The documentation for other medals backs up Miles’s assessment of the day’s horrors: One medal was for leading 20 men into a ravine, where women and children were later found dead or wounded, and another was for using a howitzer to lob explosives onto women and children in a ravine.

In 1990, Rep. Tim Johnson (D-S.D.), now retired (not related to Dusty Johnson), authored an official Congressional expression of “deep regret” for the massacre. The resolution called for a new beginning, including support for American Indian self-determination and “a recognition of the valuable contribution of Indian cultures, traditions, and values to the history and fabric of American society.”

Despite efforts like Tim Johnson’s, the view of indigenous people that engendered the horrors of Wounded Knee persists in some areas. In 1890, a South Dakota newspaper editorial came out for “total annihilation” of Native Americans. During most of 2016, the world watched aghast as North Dakota responded violently to demonstrations against an oil pipeline being built across the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation’s water supply. Heavily armed police officers and oil-company private security agents attacked unarmed civilians — women as well as men, elders as well as younger adults — with dogs, rubber bullets, mace, tear gas, batons, and water cannons deployed in sub-freezing temperatures.

According to Semans, “In this time of duly heightened sensitivity to violence against women and children, in a political era where national leaders appear to be willing to bring front and center discussion of the history and current issues of America’s indigenous people…the time is right to return to Wounded Knee.

“The time is right to hear the cries of my ancestors from that frozen and bloodied landscape.”